I Am Become Death, Destroyer Of Worlds

No signs point the way, but this has to be the place. It’s the only fenced-in compound with military hardware and a US flag flying overhead. In fact, it’s the only building visible, and on the prairie, you can see pretty far. My instructions are clear: park outside the gate and report to the guard. I’m a bit early, but others have already arrived. As I approach, the signs on the fence confirm that I’m in the right place: this is Minuteman Launch Control Facility Delta-01.

In 1991, the United States and Soviet Union signed the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START), and the 150 Minuteman nuclear missile sites in South Dakota were decommissioned. Almost all were destroyed, but the treaty allowed for representative sites to be preserved for historical and educational purposes, and so Delta-01, and missile silo Delta-09, were turned over to the National Park Service for preservation, to become the Minuteman Missile National Historical Site. Some humorless bureaucrat decided that arming the Park Service with a nuclear weapon was a bad idea, so the warhead was removed, which is a shame—if the Park Service were a nuclear power, it might get better funding.

Delta-01 is located on the north side of Interstate 90 at exit 127, about an hour east of Rapid City, South Dakota. No signs, on or off the highway, advertise its presence; this is a new unit in the Park Service, and they haven’t yet built everything they plan to build. You can’t just show up whenever you like—tours are by reservation, or, at least during this summer, you can come on Thursday morning, when they try to accommodate all comers. (See the Park Service site for details.) Apparently, even without signs, they are pretty much at capacity in terms of how many visitors they can handle.

The tour takes us into the building on the surface, where we see the living quarters, the kitchen and living area, and the security station. Then, we are packed into the elevator and taken down to the control bunker, 30 feet underground.

The control room is behind a door that is several feet thick. On the outside, a mural was painted by bored Air Force personnel: a Domino’s Pizza logo, with the words, “World-wide delivery in 30 minutes or less or your next one is free.” A Minuteman missile could reach its target in the Soviet Union in 30 minutes.

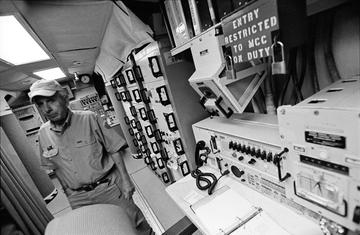

The man waiting in the control room to conduct this part of the tour is retired from the Air Force and actually worked in one of these facilities. He knows what he’s talking about, and is prepared to answer questions off the script, so it is an informative visit. The two-person staff of a launch control center would be locked inside this room for a full 24-hour shift. No one was ever allowed to be alone in this room, and they didn’t leave until relieved by another two-person crew.

Apparently, this was a choice assignment: the room is nice and quiet, and not much ever happened, so they could use the time to read, study for an advanced degree, and so on. One bunk is provided so the crew can take turns sleeping. The hardware is wonderful Cold War era technology; I would have loved to sit down and play with it, but I doubt that would be allowed.

There are no missile silos at Delta-01, nor any of the control centers. The silos are located miles away, for survivability—not of the crew, but of the missiles. If the control center were destroyed, any other control center in the area had the ability to launch this control center’s missiles; if all of them were destroyed, the missiles could be launched from the Looking Glass command planes that were in the air 24 hours a day, every day for decades.

The locations of these sites were never a secret—in fact, the locals were sometimes given tours even while they were operational. The Soviet Union was going to find them anyway, and the whole idea of the Minuteman program was that the missiles could be launched before anyone could do anything to stop them. It didn’t matter that they were targeted by enemy missiles; by the time those got here, ours would be there. Mutual Assured Destruction.

My next stop is the Delta-09 missile silo. The silo is located on the south side of I-90 at exit 116, just west of Wall, and is visible from the highway. I am amused at the sign on the exit ramp pointing the way to the “Missile Silo.”

The silo door is open, and covered with glass so you can look in and see the missile. It’s like something out of a movie; you expect Jack Bauer to show up at any moment.

A retired Air Force officer who worked on the Looking Glass flights and elsewhere in the Minuteman program was on hand when I arrived to give an informative and entertaining talk and answer questions. The silo sites were unmanned, but had motion detectors and other security measures, and apparently the Air Force security people spent a lot of time rushing out to silos and shooing away the rabbits or birds that had triggered the sensors. There was never any enemy action at these sites, but they still had to come out in an armored vehicle (one of which is on display here) loaded for bear.

These sites were all run out of Ellsworth Air Force Base, and after leaving Delta-09, this is my next stop. Ellsworth, just outside Rapid City, is home to a B-1B bomber squadron. These planes can launch from here to carry out bombing missions in Afghanistan, and have done so, a demonstration of the projection of military power that is quite awe-inspiring: flight crews can carry out combat missions in Asia and then come home when they’re finished. (They normally operate from a forward base, though.)

Ellsworth is also home to the South Dakota Air and Space Museum, a free museum with military planes of all kinds on display outside, and exhibits inside like missiles, cockpit simulations, and helicopters. More interesting, though, is the $7 bus tour onto the base itself, centered around a visit to the base’s Minuteman missile silo.

If you’re on the lam, you’ll want to avoid this tour: it’s a military base, so you must present a driver’s licence or passport to get in, and all are run through NCIC and who knows what else. While we wait for this process, our guide tells us of people who have been removed from the bus at this point because there were warrants for their arrest. Since the guards are military and can’t arrest civilians, if this becomes necessary the entire tour has to sit and wait for the local police to come, so he was probably preparing us for a wait should this happen.

The missile silo on the base was a training facility that never actually had the ability to launch a missile, so it didn’t need to be destroyed under the terms of the START treaty. It is also equipped with stairs, which wouldn’t be present at a real silo, making access by larger tour groups practical.

We go down into the silo, where the missile itself is surrounded by the equipment used to target and launch it. The “For Training Only” label on the missile only slightly degrades the experience—you’re in a silo with a nuclear missile, after all, and that’s not something you get to see every day.

Our guide, yet another retired Air Force guy, explains how everything would have worked. Normally, the only time anyone would go into a silo is if something broke. Nothing in a silo was ever repaired, only replaced—if it broke, it wasn’t good enough to stay. And the launching of the missile would destroy everything in the silo, so it was a one-time-use deal. If it were used, no one would much care about the condition of the silo after that.

Outside this silo, a “transporter-erector” vehicle, used to bring missiles to their silos, is displayed.

Ellsworth doesn’t have an underground launch control center; instead, the museum has a display of what one looked like, complete with dummies at the controls.

If you’re in the Badlands or Black Hills area, these sites offer a rare glimpse into Cold War history.